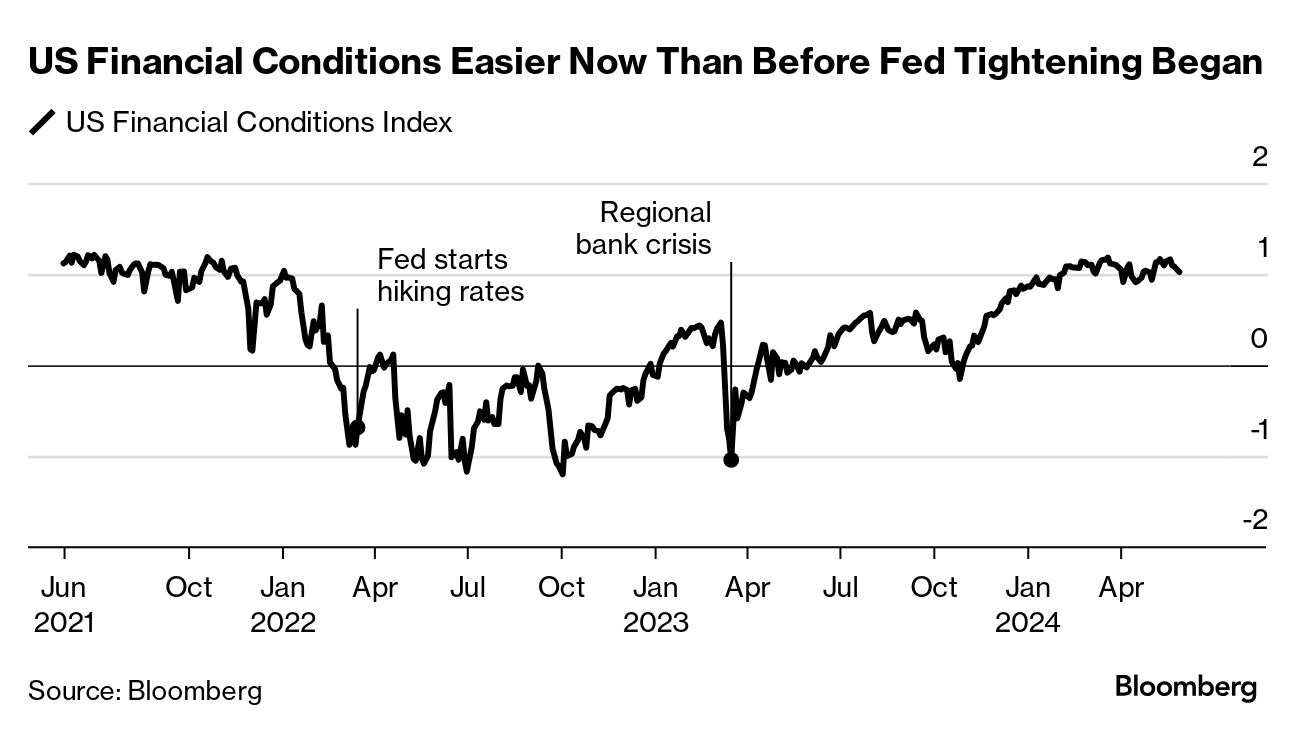

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell explained last October that monetary policy works through the channel of financial conditions, a broad term that includes a mix of asset prices and interest rates. As that responds to Fed actions, they shape the economy, including jobs and inflation. And in Powell's assessment, financial conditions are sufficiently tight that, over time, inflation will get back on a path to the Fed's 2% target. (Just how far from the target will become apparent Friday morning, with the release of the Fed's preferred gauge — the PCE price index.) The thing is, most gauges of financial conditions show a notable easing since last autumn. That's thanks in large part to a soaring stock market that's sent indexes to record highs, along with rallies in corporate bonds that have sent premiums to historically cheap levels. In fact, Bloomberg's index of financial conditions shows that they are easier now than before policymakers began jacking up interest rates more than two years ago.  Source: Bloomberg Even the Fed's own "impulse on growth" measure is now hovering around the easiest level in a couple of years. Recent levels "suggest financial conditions are applying just a mild brake on activity," Sal Guatieri, senior economist at BMO Capital Markets, wrote in a note Thursday. "Another version of this metric, based on one-year changes in financial conditions, suggests the foot may already have shifted to the gas pedal, opening the door for firmer growth in the year ahead," Guatieri says. But there's important context: these indexes are all based on price. In other words, they don't represent the magnitude of flows of credit. And gauges of the quantity of credit "tell a different story," according to JPMorgan Chase chief US economist Michael Feroli. "Growth of credit extended by the financial system looks anemic." In fact, the amount of credit extended to US households and businesses, measured as a ratio of GDP, has recently trended at remarkably low levels, rarely seen in data going back to the 1960s, according to JPMorgan analysis. Part of that is thanks to the tight housing market. Sales of existing homes are at historically depressed levels, so there's not a great deal of demand for home loans just now. Businesses have also been reducing debt, after accounting for inflation, rather than raising net new financing. And equity issuance, relative to GDP, "was the lowest on record" over the last two years, Feroli wrote. The Fed's high interest-rate settings help explain that. All of which goes to suggest policymakers have ballast to their argument, regardless of record stock prices. In New York Fed President John Williams's view, expressed Thursday, "the behavior of the economy over the past year provides ample evidence that monetary policy is restrictive." |

No comments