China’s new plan

Outside China, the supply problem observers worry about is the nation's industrial capacity and the danger its production is so big it will destabilize the global economy. In Beijing, the real worry is about housing.

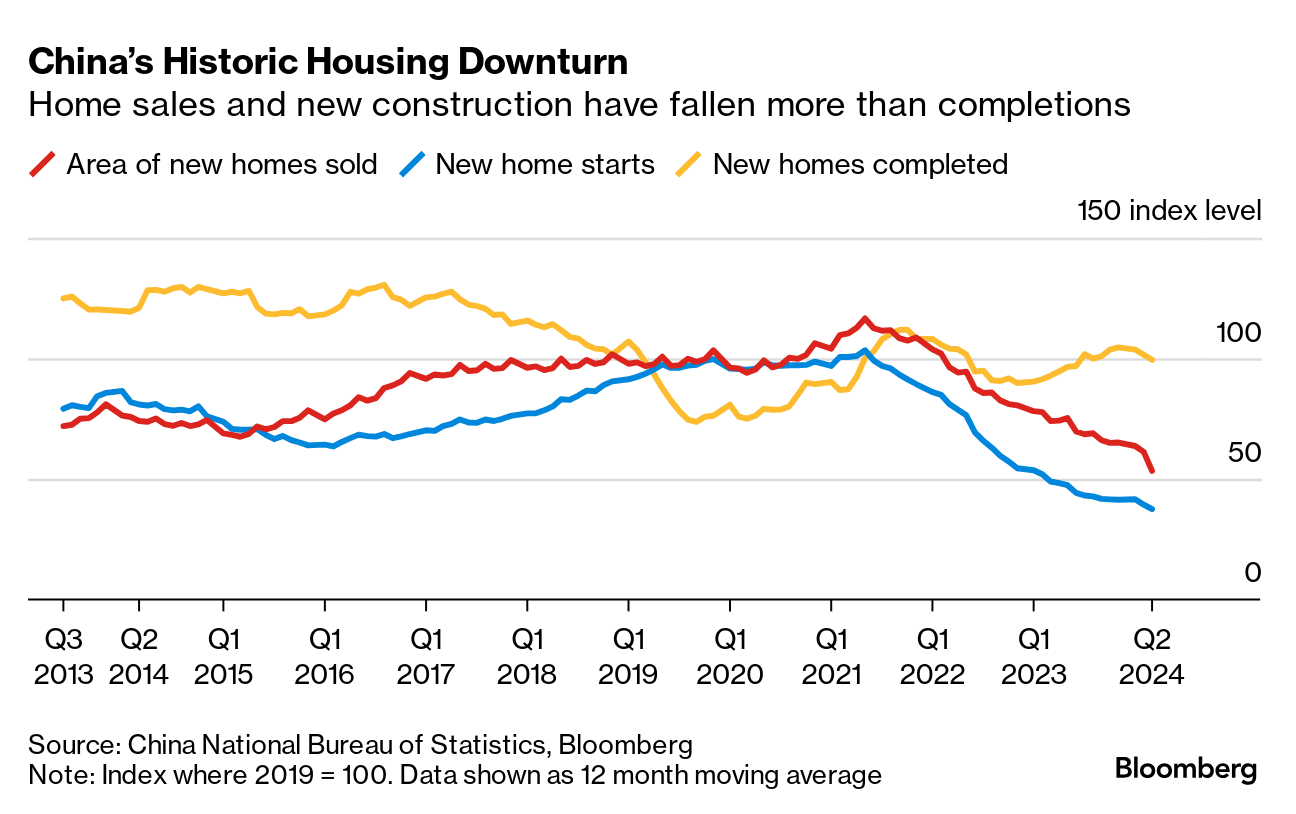

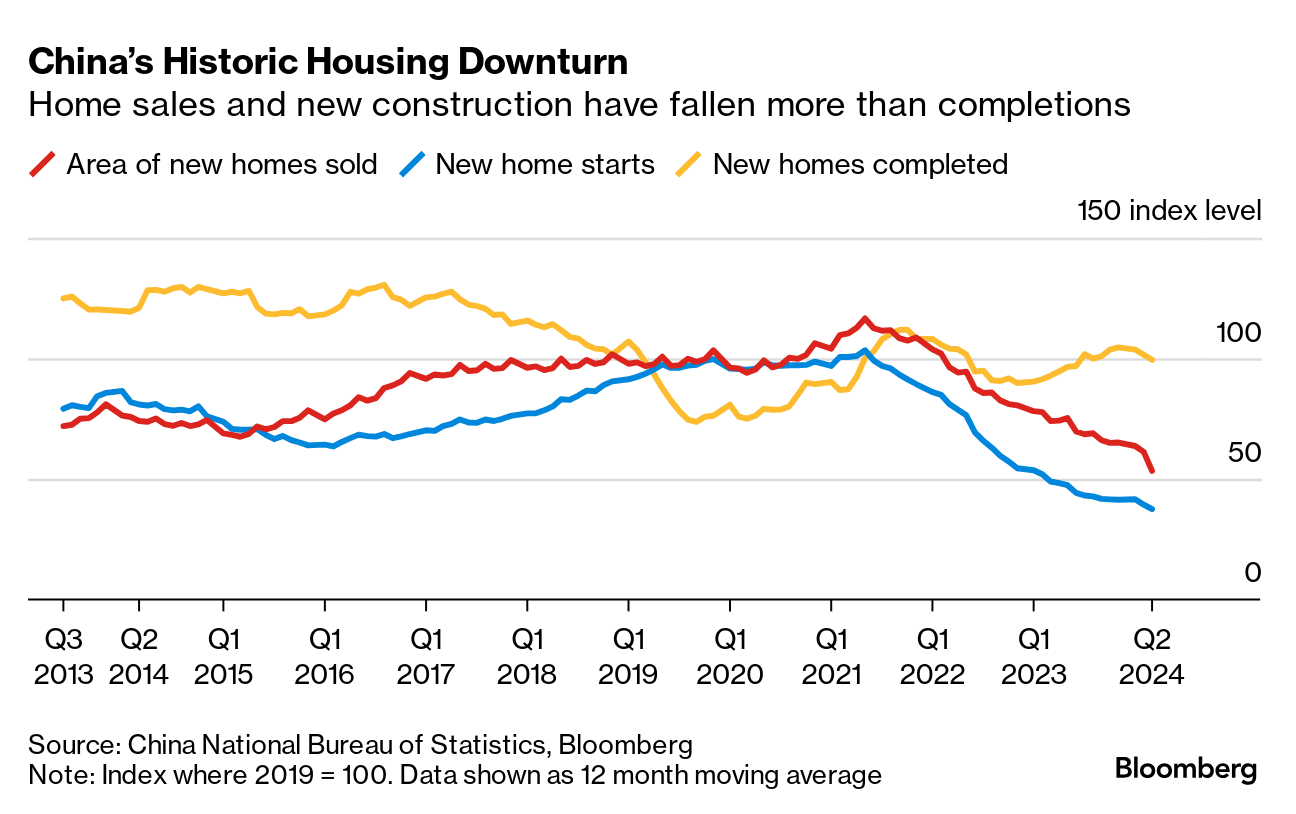

Developers for years took on leverage to snap up land and embark on grand new projects for which, it turns out, the demand just wasn't there. When the central government began to force broad deleveraging starting in the late 2010s, it sent the industry into a downward spiral.

Real-estate companies couldn't get new credit to finish off their projects. Buyers were left hanging, having forked over — by US standards — enormous down payments, without getting their new home at the end.

Read More: Wary China Consumers Face New Hurdle With Soaring Utility Costs

That spooked other potential buyers, leaving developers with all the less money to complete new apartments. Residential property sales cratered by some 31% in April versus a year before, data showed on Friday.

In Too Big to Fail, a 2011 film on the US credit meltdown, the Treasury secretary tells the Federal Reserve chair one proposed solution he'd heard was for the government to buy up all the foreclosed properties across the country, then burn them down. That would remove the supply, bolster prices on remaining homes, and kick-start the development engine again.

Read More: Chinese Banks Keep Lending Rate Unchanged After PBOC Hold

Washington didn't go down that route in the end. But Beijing is taking a step towards phase-one. On Friday, China's economic policy czar He Lifeng led a meeting aimed at mapping out a resolution. The grand plan is for local governments to buy up unsold homes. The central bank will provide loan support to commercial banks to extend credit for the effort.

Local governments can then turn the properties into affordable housing.

Investors liked the idea, sending an index of developer shares up nearly 10% on Friday.

Limited Resources

But they may be overlooking the immense challenges involved. First off, local governments hardly have fiscal space to purchase a giant overhang of property supply. One of their main sources of revenue had been — wait for it — sales of land rights to developers. That revenue stream was decimated.

Local authorities also shelled out enormous sums during Covid to implement draconian pandemic controls. Goldman Sachs estimated their total debt load last year at $23 trillion.

So the $42 billion of lending support from the People's Bank of China unveiled Friday is just simply not enough to resolve the crisis, economists said.

Game-changing measures "would likely require significantly more funding than available thus far," Goldman economists led by Lisheng Wang wrote in a note, citing earlier research that getting outstanding housing inventory back to 2018 levels would require the equivalent of more than $1 trillion.

Developers for years took on leverage to snap up land and embark on grand new projects for which, it turns out, the demand just wasn't there. When the central government began to force broad deleveraging starting in the late 2010s, it sent the industry into a downward spiral.

Real-estate companies couldn't get new credit to finish off their projects. Buyers were left hanging, having forked over — by US standards — enormous down payments, without getting their new home at the end.

Read More: Wary China Consumers Face New Hurdle With Soaring Utility Costs

That spooked other potential buyers, leaving developers with all the less money to complete new apartments. Residential property sales cratered by some 31% in April versus a year before, data showed on Friday.

In such a situation, simply lowering interest rates and reducing regulatory down payment ratios isn't going to fix the problem. Something much bigger is needed.

In Too Big to Fail, a 2011 film on the US credit meltdown, the Treasury secretary tells the Federal Reserve chair one proposed solution he'd heard was for the government to buy up all the foreclosed properties across the country, then burn them down. That would remove the supply, bolster prices on remaining homes, and kick-start the development engine again.

Read More: Chinese Banks Keep Lending Rate Unchanged After PBOC Hold

Washington didn't go down that route in the end. But Beijing is taking a step towards phase-one. On Friday, China's economic policy czar He Lifeng led a meeting aimed at mapping out a resolution. The grand plan is for local governments to buy up unsold homes. The central bank will provide loan support to commercial banks to extend credit for the effort.

Local governments can then turn the properties into affordable housing.

Investors liked the idea, sending an index of developer shares up nearly 10% on Friday.

Limited Resources

But they may be overlooking the immense challenges involved. First off, local governments hardly have fiscal space to purchase a giant overhang of property supply. One of their main sources of revenue had been — wait for it — sales of land rights to developers. That revenue stream was decimated.

Local authorities also shelled out enormous sums during Covid to implement draconian pandemic controls. Goldman Sachs estimated their total debt load last year at $23 trillion.

So the $42 billion of lending support from the People's Bank of China unveiled Friday is just simply not enough to resolve the crisis, economists said.

Game-changing measures "would likely require significantly more funding than available thus far," Goldman economists led by Lisheng Wang wrote in a note, citing earlier research that getting outstanding housing inventory back to 2018 levels would require the equivalent of more than $1 trillion.

No comments