Debt danger zone

The Group of Seven finance chiefs meeting this week declined to include fiscal sustainability on their agenda, despite inflated debt loads and continuing sizeable deficits in multiple member nations.

One school of thought says, indeed, there's little need to worry. Japan has the largest burden of them all, yet has the lowest borrowing costs and little effort rolling over its debt. Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate in economics, said Wednesday that "maybe France in 1926" is one of the few examples of a true debt crisis for a country borrowing in its own currency.

Another school says that, even if there's no apparent problem today, it leaves national Treasuries vulnerable, with diminished "fiscal space" to address emergencies. That's something Maya MacGuineas, head of the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, warns about.

A crisis comes "when people would rather put their money somewhere else than here," and that appetite "can change very abruptly," she said earlier this month.

That's something then-UK Prime Minister Liz Truss found out in September 2022, when her government triggered a crisis with plans for unfunded tax cuts. The Bank of England had to step into the bond market to avert a meltdown.

Future Shock

Michael Feroli, chief US economist at JPMorgan, suggests it would be unwise to think a Truss-type event couldn't happen in the US.

Not only has the supply of federal debt soared, but the willingness and capacity of primary dealers in Treasuries to trade the securities has failed to increase by the same magnitude. That leaves the market vulnerable to shocks — as happened when Covid hit in March 2020, and the Fed had to step in with massive buying.

The worry is that the infrastructure isn't there that "would guarantee that we don't have some problems, perhaps, that echo what happened with Liz Truss' mini-budget two years ago," Feroli said at a May 13 conference.

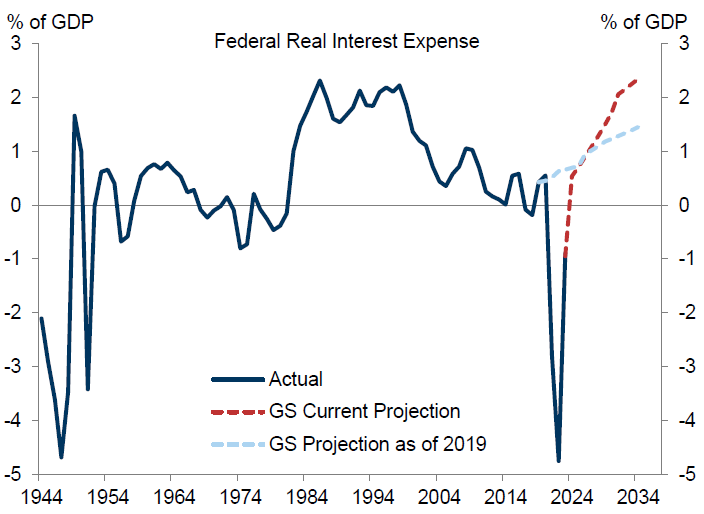

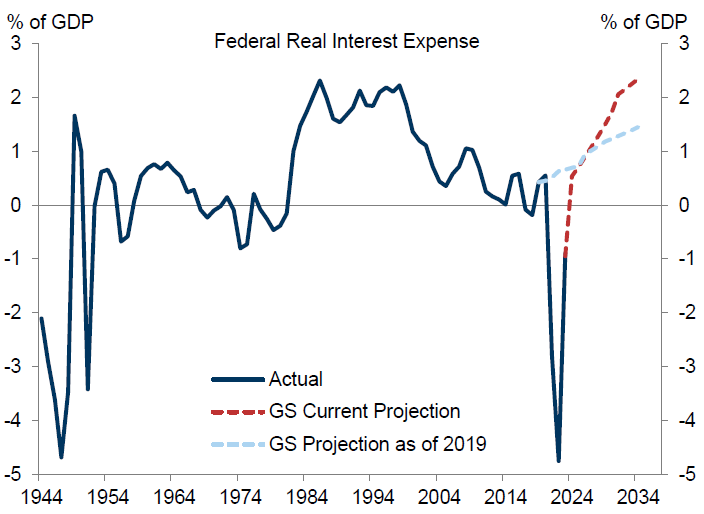

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who's attending the G-7 conference, has downplayed the debt-to-GDP ratio — now roughly 100% — as a concern. She says what matters is net debt interest payments after adjusting for inflation. Last year, she said that a ratio of 1% was "absolutely fine, there's nothing worrisome about that."

On Wednesday, Goldman Sachs economists updated their long-term forecasts. They see the Yellen-preferred ratio hitting 2.3% in 2034 — a level that also surpasses the 2% guideline suggested by top former Obama administration economic officials.

Baseline projections also don't account for things like unexpected wars. This week's venue for the G-7 finance meeting serves as a reminder of such dangers: Stresa, Italy, in 1935 played host to a summit to discuss a response to Nazi Germany's plans for rearmament.

Need-to-Know Research

Showcasing that the "higher-for-longer" narrative isn't just a US story, a slew of economics teams at major banks has rolled back forecasts for the first interest-rate cut by the Bank of England.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc, Morgan Stanley, HSBC Holdings Plc and Barclays Plc all are among those now expecting the BOE to lower borrowing costs in August, rather than at its upcoming policy meeting in June. The key rate has been at 5.25% since August, its highest since 2008.

June "was always likely to be a close call and and punchy inflation data may have knocked out the prospect of a cut," said Simon Wells at HSBC — referring to data on Wednesday showing that inflation slowed less than expected in April, particularly in the services sector.

One school of thought says, indeed, there's little need to worry. Japan has the largest burden of them all, yet has the lowest borrowing costs and little effort rolling over its debt. Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate in economics, said Wednesday that "maybe France in 1926" is one of the few examples of a true debt crisis for a country borrowing in its own currency.

Janet Yellen speaks at a press conference in Stresa, Italy, on May 23. Photographer: Gabriel Bouys/AFP/Getty Images

Another school says that, even if there's no apparent problem today, it leaves national Treasuries vulnerable, with diminished "fiscal space" to address emergencies. That's something Maya MacGuineas, head of the bipartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, warns about.

A crisis comes "when people would rather put their money somewhere else than here," and that appetite "can change very abruptly," she said earlier this month.

That's something then-UK Prime Minister Liz Truss found out in September 2022, when her government triggered a crisis with plans for unfunded tax cuts. The Bank of England had to step into the bond market to avert a meltdown.

Future Shock

Michael Feroli, chief US economist at JPMorgan, suggests it would be unwise to think a Truss-type event couldn't happen in the US.

Not only has the supply of federal debt soared, but the willingness and capacity of primary dealers in Treasuries to trade the securities has failed to increase by the same magnitude. That leaves the market vulnerable to shocks — as happened when Covid hit in March 2020, and the Fed had to step in with massive buying.

The worry is that the infrastructure isn't there that "would guarantee that we don't have some problems, perhaps, that echo what happened with Liz Truss' mini-budget two years ago," Feroli said at a May 13 conference.

US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who's attending the G-7 conference, has downplayed the debt-to-GDP ratio — now roughly 100% — as a concern. She says what matters is net debt interest payments after adjusting for inflation. Last year, she said that a ratio of 1% was "absolutely fine, there's nothing worrisome about that."

Source: Department of the Treasury, Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

On Wednesday, Goldman Sachs economists updated their long-term forecasts. They see the Yellen-preferred ratio hitting 2.3% in 2034 — a level that also surpasses the 2% guideline suggested by top former Obama administration economic officials.

Baseline projections also don't account for things like unexpected wars. This week's venue for the G-7 finance meeting serves as a reminder of such dangers: Stresa, Italy, in 1935 played host to a summit to discuss a response to Nazi Germany's plans for rearmament.

Need-to-Know Research

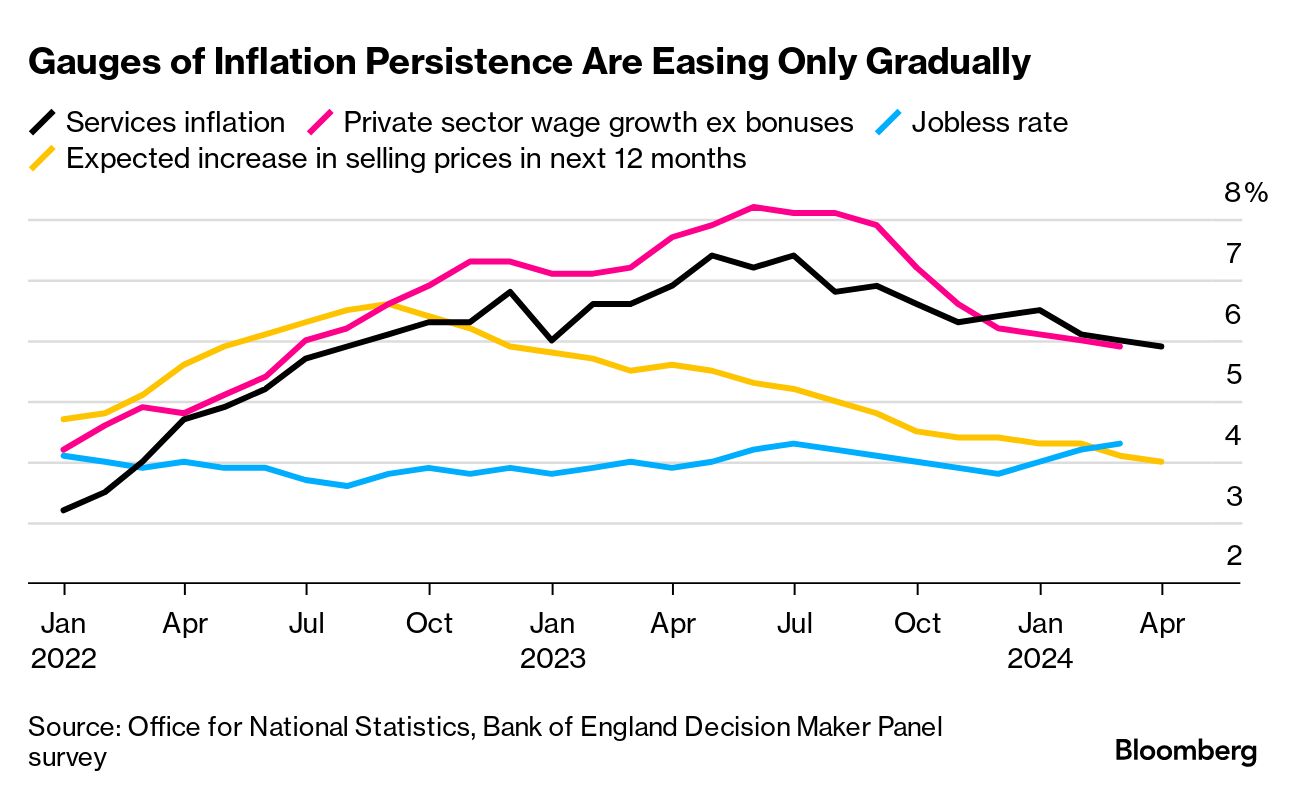

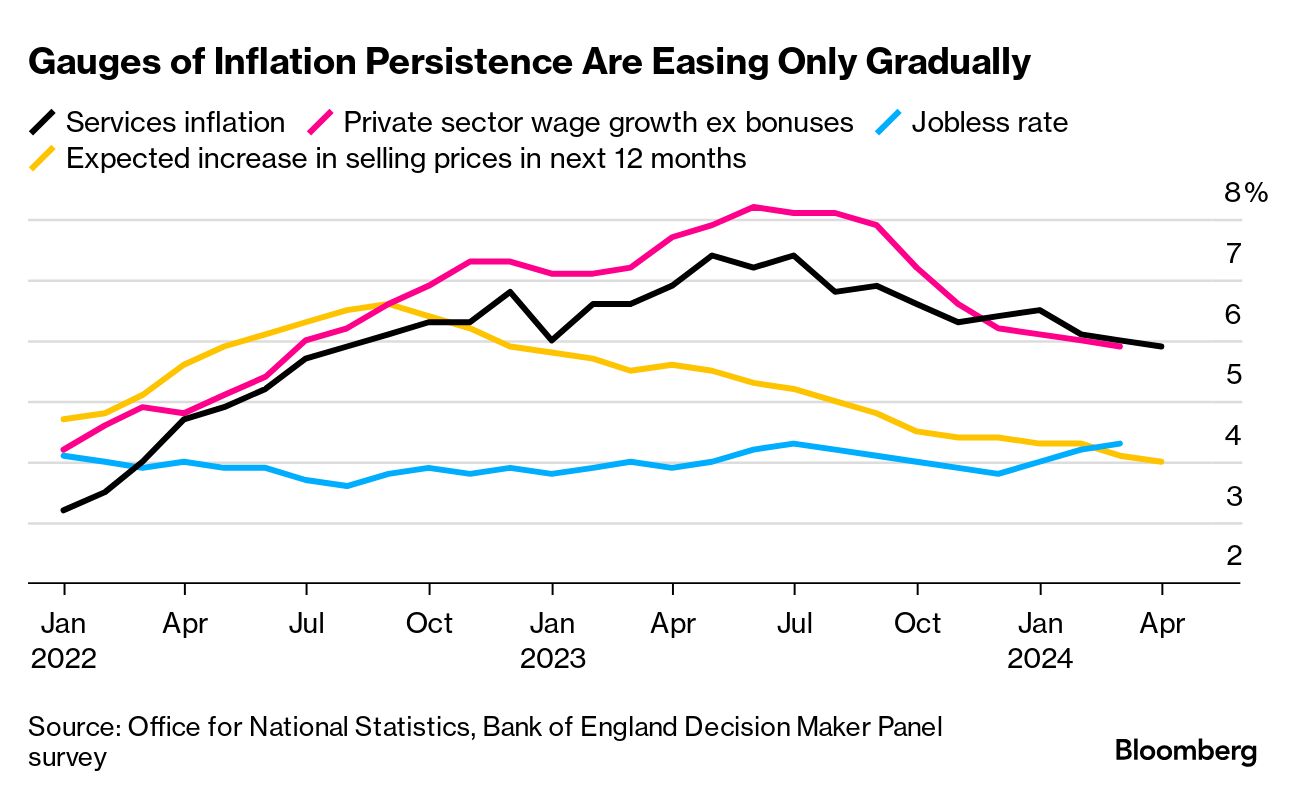

Showcasing that the "higher-for-longer" narrative isn't just a US story, a slew of economics teams at major banks has rolled back forecasts for the first interest-rate cut by the Bank of England.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc, Morgan Stanley, HSBC Holdings Plc and Barclays Plc all are among those now expecting the BOE to lower borrowing costs in August, rather than at its upcoming policy meeting in June. The key rate has been at 5.25% since August, its highest since 2008.

June "was always likely to be a close call and and punchy inflation data may have knocked out the prospect of a cut," said Simon Wells at HSBC — referring to data on Wednesday showing that inflation slowed less than expected in April, particularly in the services sector.

No comments