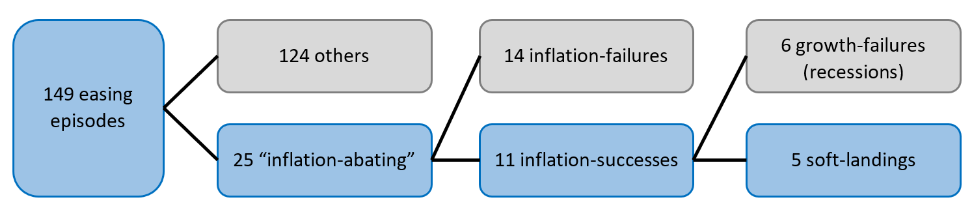

The resilience of the US labor market in the face of the Federal Reserve's historically high interest rates has spurred some to question the accuracy of payrolls data. New figures on Wednesday reinforced that skepticism. The Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages from the Bureau of Labor Statistics covers more than 95% of US jobs and is drawn from unemployment insurance tax records filed by more than 12 million establishments. That's a much bigger data-set than the number of institutions surveyed for the monthly payrolls figures, which includes about 119,000 businesses and government agencies. The new figures suggest payroll increases were about 60,000 less per month last year than the roughly 250,000 average that the official tally shows. By comparison, Friday's May payrolls report is projected to post a gain of about 185,000. That doesn't indicate the economy is crashing. It's more like the picture of the job market goes from "boomy" to "healthy," according to economist Guy Berger at the Burning Glass Institute, an employment analysis firm. But it could suggest that the job market isn't as hot as some at the Fed had feared. If indeed the pace of employment gains has already slowed more substantially than thought, that strengthens the case for rate reductions sooner rather than later. "The Fed could be late to cut rates — cutting only when the labor market already is far into a downward spiral," said Anna Wong, chief US economist at Bloomberg Economics. (Read Anna's note on the Bloomberg terminal here.) The additional challenge for Fed officials is that it will take time to reconcile the data. Wednesday's figures will be used to benchmark the monthly payrolls figures in February, and the BLS provides an initial estimate of that revision in August. More often than not, central banks that start cutting interest rates as inflation starts to slow end up failing to contain consumer prices, according to analysis of the historical record by a pair of Federal Reserve Board economists. Francois de Soyres and Zina Saijid found 25 episodes in 13 advanced economies where policymakers eased policy against a backdrop where core inflation was on a downward trajectory, but still above a desired level. In other words, similar to where many central banks are today. They reviewed data over a period from 1960 to 2019.  Source: Francois de Soyres and Zina Saijid And of those 25, only 11 resulted in "inflation successes," the duo wrote in a recent note. Even more sobering for today's central bankers: just five of those successes can be counted as "soft landings," where prices were brought under control without a technical recession.  |

No comments