Japan’s sun rises

James Kuffner, a former Google executive recruited eight years ago to help run a Toyota innovation hub in Japan, brought a radical idea with him for his new colleagues: wear what you like at work.

He quickly ran into problems. The human resources department informed him that Japanese staff were afraid their neighbors would assume they'd been fired if they left home every morning dressed in casual clothes rather than the ubiquitous business suit.

Kuffner found a solution: lockers to let employees change out of their commute suits. But the consternation showcased a national work culture that in many ways can inhibit change. It was often said that Japan had the best economy for the 1980s: an emphasis on error-free, process-focused high-quality manufacturing. But supposedly not for a software-dominant 21st century that rewarded less linear avenues of thinking.

What's now becoming clear, however, is that a slew of structural changes have taken root in Japan—including cultural shifts that are opening up Asia's No. 2 economy in ways few would have expected a decade or so ago. "Animal spirits" may be taking root, enhancing Japan's appeal to investors and neighboring nations alike.

How some cultural conventions in Japan have held back progress has been widely explored. One example was the systematic manipulation of medical-school test scores in order to keep the number of female students down, out of concern women would work less for reasons including having children.

Discriminating against top performers based on gender stereotypes is hardly a recipe for success in any country. Japan's history of not being very receptive to foreigners has also been seen as a major restraint on economic growth.

In a developed nation where the fertility rate is far below the level needed to keep the population stable, preventing women and foreigners from joining the workforce is a recipe for disaster.

It took Japan's economic stagnation in the 1990s and 2000s to lay the groundwork for a shift in thinking on many fronts—from economic to defense to even social policies. And it gave traction to Shinzo Abe, the late prime minister who pushed for a wholesale rethinking of policy during a term that spanned almost eight years.

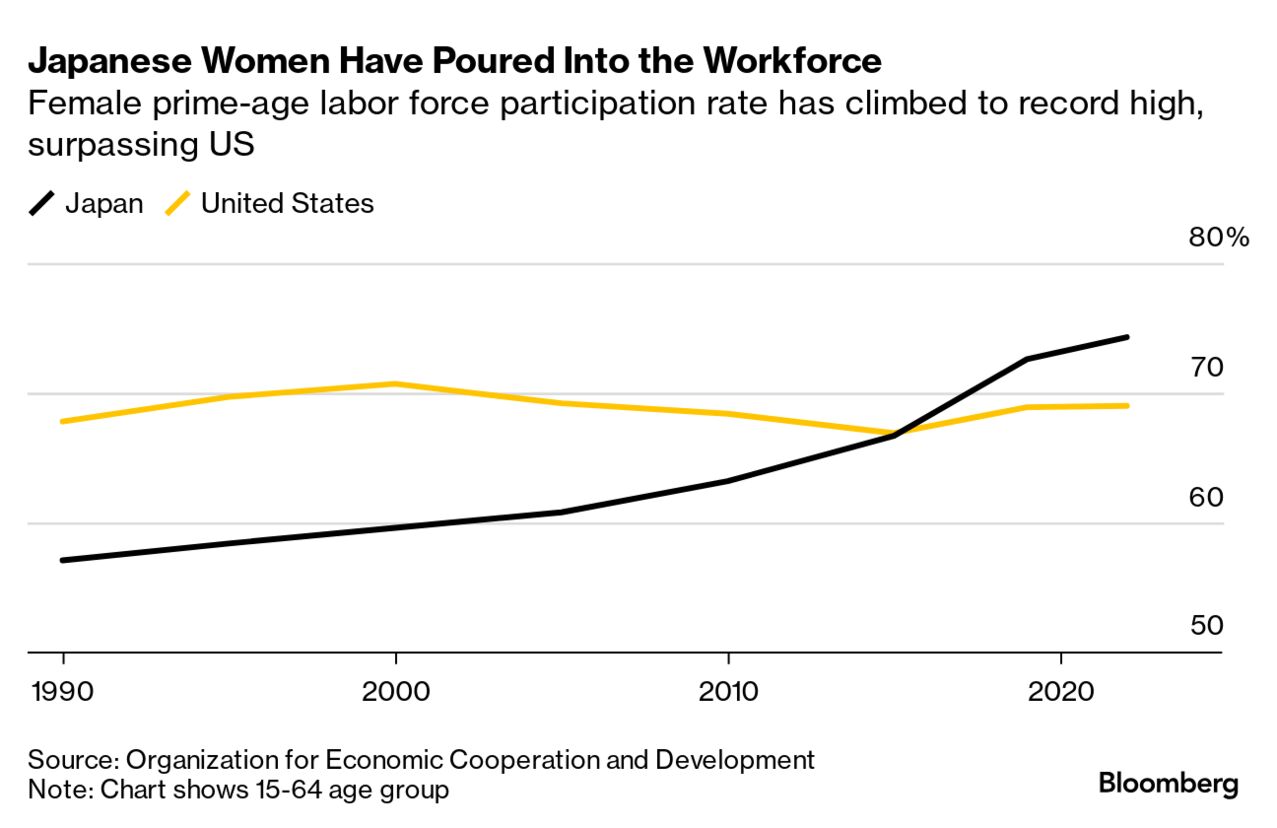

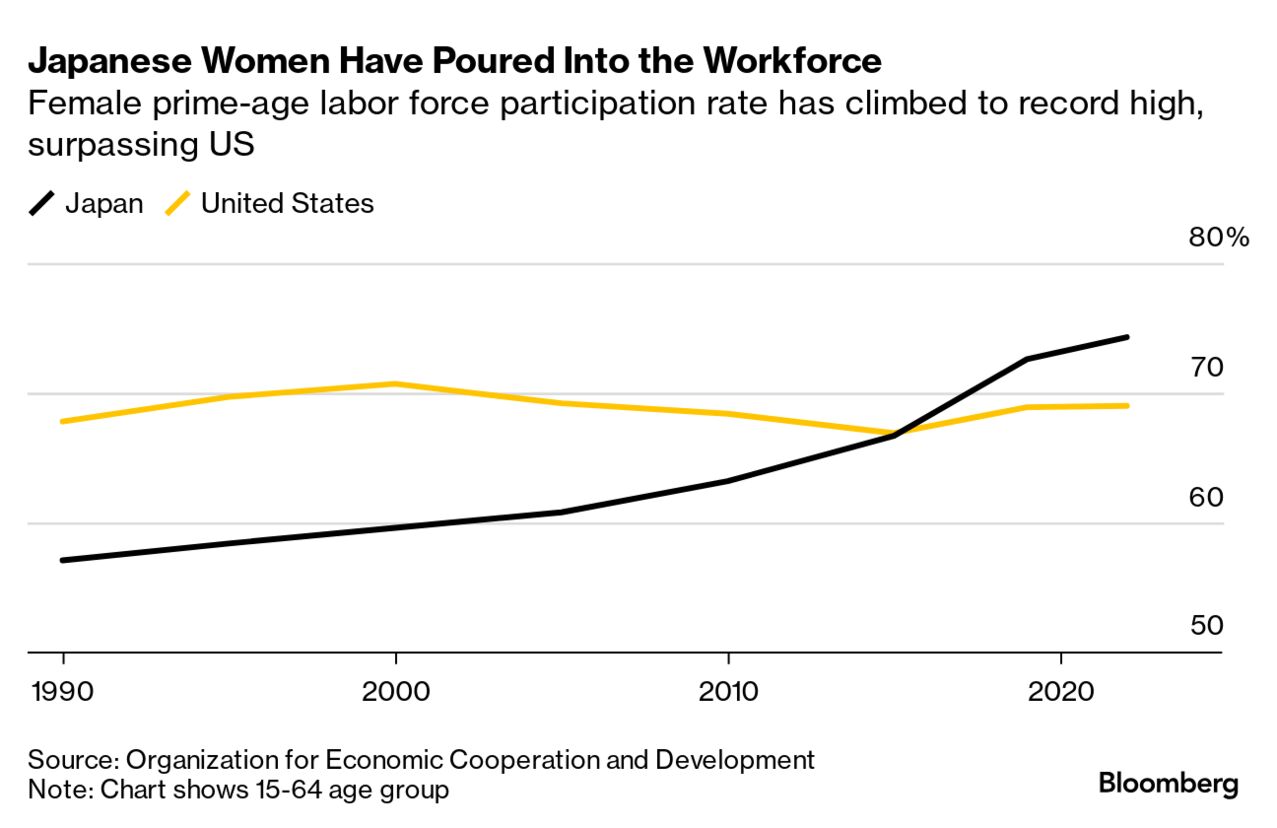

Abe's shake-up included raising the role of women—dubbed womenomics. It was more than just a slogan: the prime-working-age female labor-force participation rate soared to a record of 74.3% by 2022, more than 10 percentage points above where it had trended before the advent of "Abenomics." (By contrast, the US rate has gone down.)

Abe's team also took steps to loosen rules on foreign workers—while minding the political sensitivity of change in this area. An analogy was made to baseball: when foreign players were given a limited entry into Japan's league, there was a public stir, but in time fans cheered on the non-native Japanese players. Perhaps the same could happen with attitudes toward immigration.

The result: last year, the number of foreign workers hit a record 2.04 million, up 12.4% from the year before. "Japan is entering an era of mass foreign immigration," said Junji Ikeda, who heads an agency that sources and supervises foreign workers.

Japan is also now luring a record number of foreign tourists, even though the number of Chinese visitors, the third-biggest group, hasn't recovered to pre-Covid levels. All those international visitors and workers will help to continuously open the country up.

An Indonesian worker at a factory in Oizumi, Japan, in 2018. Photographer: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP

The incorporation of and increasing respect for differences in Japanese society is manifesting itself in other ways as well. Japan's top business lobby, the Keidanren, this week urged the government to embrace letting married couples have separate surnames.

Last year, Japan's Supreme Court for the first time made a ruling on LGBTQ people's rights in the workplace, judging that it was illegal to restrict a transgender person from using certain bathrooms.

At a corporate level, Japan's legendary Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is offering major support for foreign companies' projects in Japan. Once known as MITI, the ministry was a mercantilist force in promoting domestic champions on the global stage starting in the 1950s. Today, it's involved in developments that feature IBM and Taiwan's TSMC.

Also emerging: a pushback against giant companies bullying their suppliers. The chair of Japan's main automaker association last month said change is afoot such that members will now accept the passing along of cost increases by their suppliers.

Another corporate change is the unwinding of cross-shareholdings of big Japanese firms, long seen by observers as reducing incentives for competition. Foreign executives for decades met with frustration in attempting to persuade Japanese customers to switch suppliers, as firms prioritized long-standing relationships with little regard to cost or efficiency.

All of these changes augur for a more flexible, more dynamic socio-economic backdrop for Japan that should provide major benefits in terms of productivity over time. While Chinese President Xi Jinping pays lip service to "reform and opening up," it's actually China's neighbor, Japan, that is putting such verbiage to effect.

For countries like those in Southeast Asia looking for a geo-economic counterweight to China, Japan's resurgence on the global scene is encouraging indeed. —Chris Anstey.

He quickly ran into problems. The human resources department informed him that Japanese staff were afraid their neighbors would assume they'd been fired if they left home every morning dressed in casual clothes rather than the ubiquitous business suit.

Kuffner found a solution: lockers to let employees change out of their commute suits. But the consternation showcased a national work culture that in many ways can inhibit change. It was often said that Japan had the best economy for the 1980s: an emphasis on error-free, process-focused high-quality manufacturing. But supposedly not for a software-dominant 21st century that rewarded less linear avenues of thinking.

What's now becoming clear, however, is that a slew of structural changes have taken root in Japan—including cultural shifts that are opening up Asia's No. 2 economy in ways few would have expected a decade or so ago. "Animal spirits" may be taking root, enhancing Japan's appeal to investors and neighboring nations alike.

James Kuffner Photographer: Akio Kon/Bloomberg

How some cultural conventions in Japan have held back progress has been widely explored. One example was the systematic manipulation of medical-school test scores in order to keep the number of female students down, out of concern women would work less for reasons including having children.

Discriminating against top performers based on gender stereotypes is hardly a recipe for success in any country. Japan's history of not being very receptive to foreigners has also been seen as a major restraint on economic growth.

In a developed nation where the fertility rate is far below the level needed to keep the population stable, preventing women and foreigners from joining the workforce is a recipe for disaster.

It took Japan's economic stagnation in the 1990s and 2000s to lay the groundwork for a shift in thinking on many fronts—from economic to defense to even social policies. And it gave traction to Shinzo Abe, the late prime minister who pushed for a wholesale rethinking of policy during a term that spanned almost eight years.

Abe's shake-up included raising the role of women—dubbed womenomics. It was more than just a slogan: the prime-working-age female labor-force participation rate soared to a record of 74.3% by 2022, more than 10 percentage points above where it had trended before the advent of "Abenomics." (By contrast, the US rate has gone down.)

Abe's team also took steps to loosen rules on foreign workers—while minding the political sensitivity of change in this area. An analogy was made to baseball: when foreign players were given a limited entry into Japan's league, there was a public stir, but in time fans cheered on the non-native Japanese players. Perhaps the same could happen with attitudes toward immigration.

The result: last year, the number of foreign workers hit a record 2.04 million, up 12.4% from the year before. "Japan is entering an era of mass foreign immigration," said Junji Ikeda, who heads an agency that sources and supervises foreign workers.

Japan is also now luring a record number of foreign tourists, even though the number of Chinese visitors, the third-biggest group, hasn't recovered to pre-Covid levels. All those international visitors and workers will help to continuously open the country up.

An Indonesian worker at a factory in Oizumi, Japan, in 2018. Photographer: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP

The incorporation of and increasing respect for differences in Japanese society is manifesting itself in other ways as well. Japan's top business lobby, the Keidanren, this week urged the government to embrace letting married couples have separate surnames.

Last year, Japan's Supreme Court for the first time made a ruling on LGBTQ people's rights in the workplace, judging that it was illegal to restrict a transgender person from using certain bathrooms.

At a corporate level, Japan's legendary Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is offering major support for foreign companies' projects in Japan. Once known as MITI, the ministry was a mercantilist force in promoting domestic champions on the global stage starting in the 1950s. Today, it's involved in developments that feature IBM and Taiwan's TSMC.

Also emerging: a pushback against giant companies bullying their suppliers. The chair of Japan's main automaker association last month said change is afoot such that members will now accept the passing along of cost increases by their suppliers.

Another corporate change is the unwinding of cross-shareholdings of big Japanese firms, long seen by observers as reducing incentives for competition. Foreign executives for decades met with frustration in attempting to persuade Japanese customers to switch suppliers, as firms prioritized long-standing relationships with little regard to cost or efficiency.

All of these changes augur for a more flexible, more dynamic socio-economic backdrop for Japan that should provide major benefits in terms of productivity over time. While Chinese President Xi Jinping pays lip service to "reform and opening up," it's actually China's neighbor, Japan, that is putting such verbiage to effect.

For countries like those in Southeast Asia looking for a geo-economic counterweight to China, Japan's resurgence on the global scene is encouraging indeed. —Chris Anstey.

No comments