Rates reset

Amid all the doubts about how restrictive the Federal Reserve's policy setting is and where inflation may be headed in coming months, there's one clear reality: the longer interest rates stay where they are, the more pain they will inflict on those who have to refinance low-cost loans.

"They're coming," says Peter Newlin, a senior executive of Gastamo Group, says with regard to higher borrowing costs. The Denver-based restaurant company is set to see its loan rates double to as much as 8% starting in two years.

Others are already, or outright failing to roll over their credit. Default rates on loans to small business in February hit an annual rate of 3.2%, matching their highest level in at least a decade, according to the credit bureau Equifax.

The impact is visible in investment spending, which is among the most interest-rate sensitive of economic activities:

Capital investments in manufacturing will rise by only 3.9% this year, down from a January estimate of 6.7%, S&P Global Market Intelligence projects.

The Institute for Supply Management's latest economic forecast showed company leaders expect only a 1% increase in capital outlays this year, down from an estimate of almost 12% last December.

The Association For Manufacturing Technology last month reported that average monthly orders from contract machine shops are 11.3% lower in 2024 than in 2023, reflecting a shift by customers "away from longer-term procurement cycles."

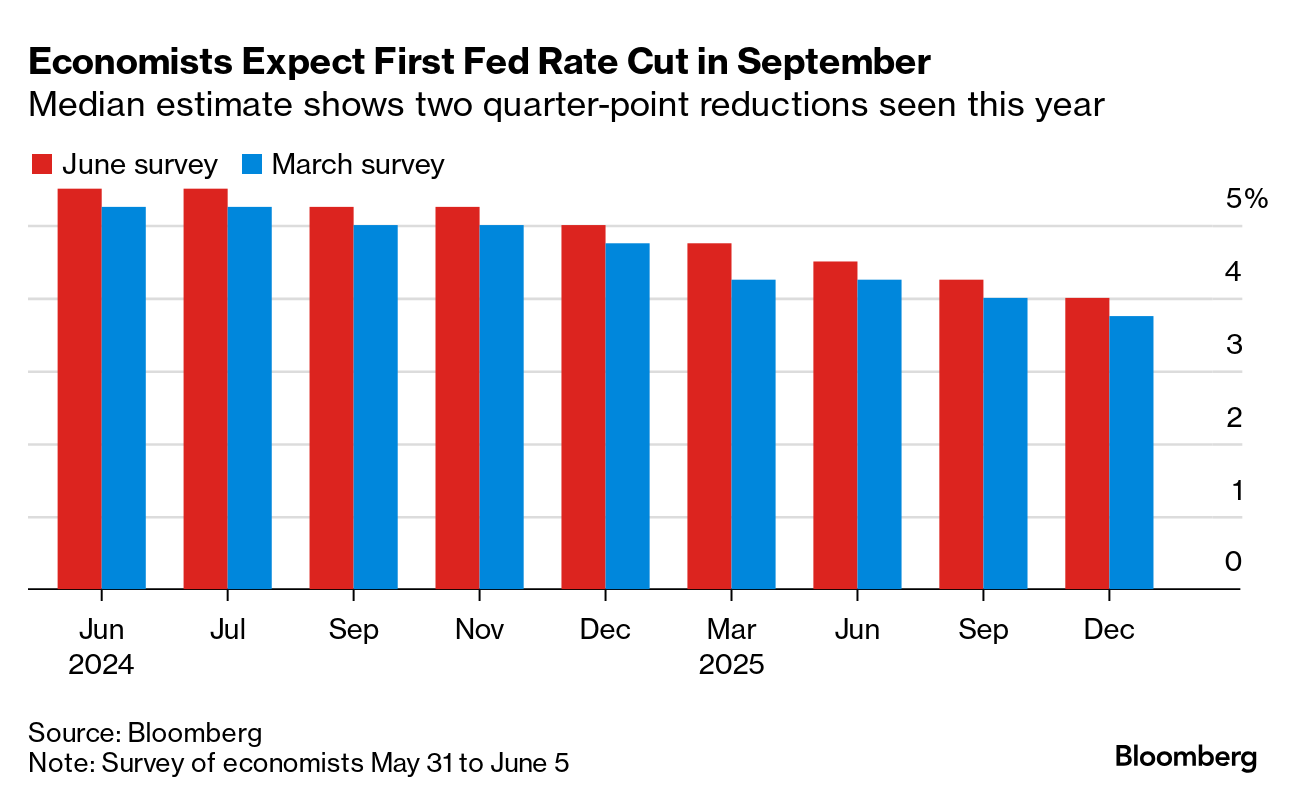

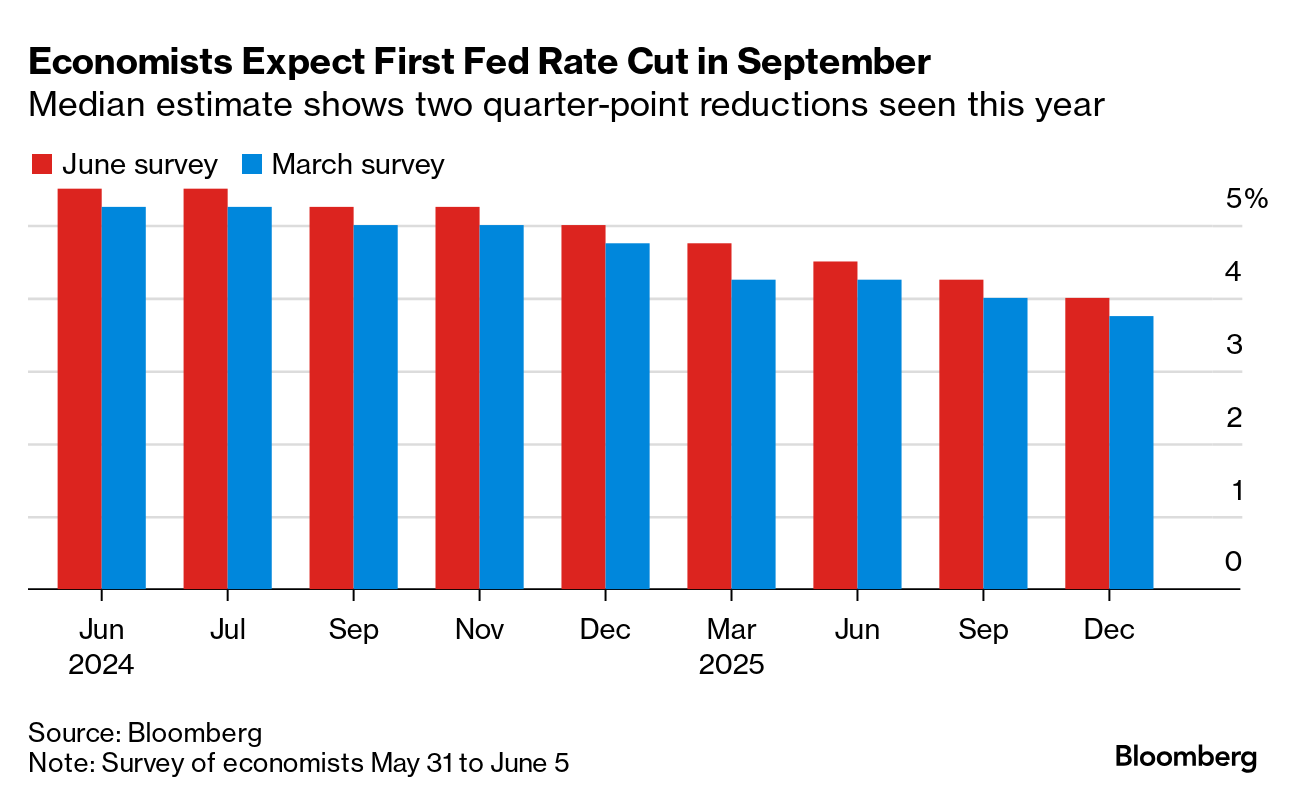

The backdrop for those changes in plans and projections: a sharp shift in expectations for interest rates in 2024.

Back in December, financial markets were anticipating about 1.5 percentage points of rate cuts by the Fed. Today, less than 0.5 percentage point is priced in, which would leave the Fed's benchmark near 5% at year-end, or almost triple the average of the past two decades.

"You definitely have to pull back the reins when interest rates are high," said Patrick Curry, president of the Michigan-based Fullerton Tool Co. "We have to hold off on some of that and try to make best with the existing equipment we have."

"They're coming," says Peter Newlin, a senior executive of Gastamo Group, says with regard to higher borrowing costs. The Denver-based restaurant company is set to see its loan rates double to as much as 8% starting in two years.

Others are already, or outright failing to roll over their credit. Default rates on loans to small business in February hit an annual rate of 3.2%, matching their highest level in at least a decade, according to the credit bureau Equifax.

The impact is visible in investment spending, which is among the most interest-rate sensitive of economic activities:

Capital investments in manufacturing will rise by only 3.9% this year, down from a January estimate of 6.7%, S&P Global Market Intelligence projects.

The Institute for Supply Management's latest economic forecast showed company leaders expect only a 1% increase in capital outlays this year, down from an estimate of almost 12% last December.

The Association For Manufacturing Technology last month reported that average monthly orders from contract machine shops are 11.3% lower in 2024 than in 2023, reflecting a shift by customers "away from longer-term procurement cycles."

The backdrop for those changes in plans and projections: a sharp shift in expectations for interest rates in 2024.

Back in December, financial markets were anticipating about 1.5 percentage points of rate cuts by the Fed. Today, less than 0.5 percentage point is priced in, which would leave the Fed's benchmark near 5% at year-end, or almost triple the average of the past two decades.

"You definitely have to pull back the reins when interest rates are high," said Patrick Curry, president of the Michigan-based Fullerton Tool Co. "We have to hold off on some of that and try to make best with the existing equipment we have."

No comments